Applying a quality conscience to safety-critical major projects

Author: First published by the Chartered Quality Institute

We should all understand how to apply a quality conscience on a small scale, but how about when working on safety-critical major projects? Martin Davies, Project Quality Director, Lee Davies, HS2 Client Director, and Leigh Wakefield, Civil Nuclear Director, all at construction and engineering company Costain, draw on their cross-industry experiences to outline five key learnings for transforming the performance of infrastructure in heavily regulated environments.

Delivery of safety-critical major projects across the infrastructure ecosystem is incredibly complex – and even more so when set against a backdrop of the energy crisis and the UK government’s drive for efficiencies.

A key method in achieving this is to consider projects as a portfolio. Rather than delivering them in silos, we should actively seek to exploit opportunities for cross-fertilisation and sharing of knowledge. By implementing a systems approach and examining the synergies between projects, we can distil key learnings into actionable insights. These can be used to redraw the blueprint for successful programme delivery, ensuring that we are efficiently delivering value outcomes – while never losing sight of the fundamental imperative of assuring quality.

What does best practice look like?

There are core foundations which must be in place to assure high standards of quality. In safety-critical projects, the importance of process safety thinking needs to be established and embedded from the outset, underpinned by a strong quality culture.

What do we mean by this? It is an integrated project team, defined by a ‘one team’ mentality, with a clear vision of what success looks like and the role of each individual in realising that vision, enhancing decision-making throughout the lifecycle of the project.

Production thinking and building information modelling (BIM) techniques are at the heart of this vision. It should also incorporate standardisation, where bespoke assets are only created when absolutely necessary; where data insights are used to fuel collaborative working; and digital rehearsals maximise the opportunity for off-site assembly, testing, trialling and commissioning.

If all of these elements are brought together, clients, stakeholders and users of the infrastructure will be confident in its ability to operate safely and predictably over its lifecycle. Furthermore, while quality culture will always play a central role in improving productivity and safety on projects, it can also be used effectively to shape the culture of an organisation and be its conscience throughout operations.

Five key learnings

1. Adopt a holistic systems view

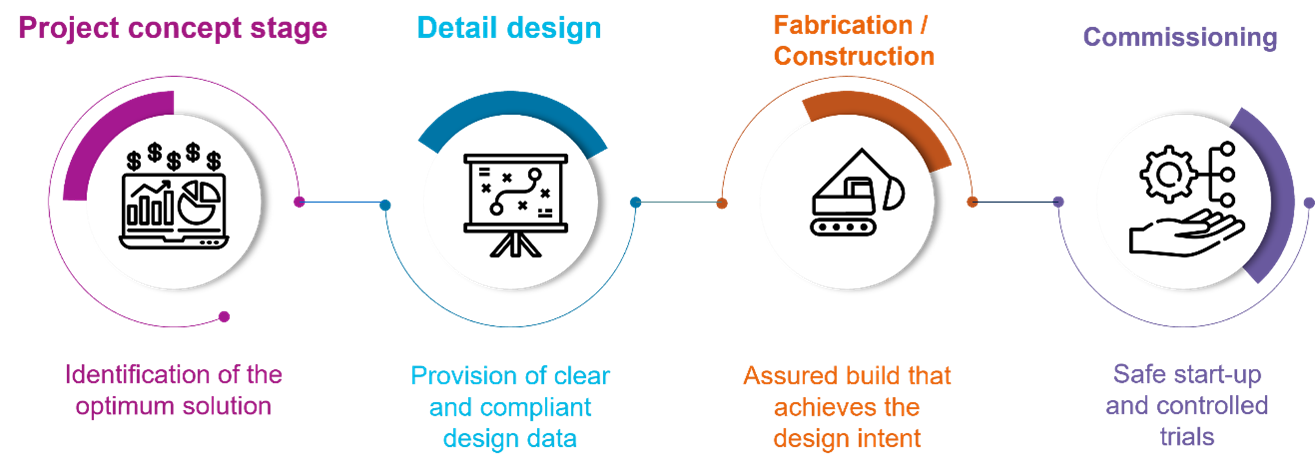

To ensure the highest standards of quality are delivered at each phase, there must be a clear understanding of the whole lifecycle requirements from the outset – proactive through-life planning is a prerequisite for success.

This shift from reactive to proactive is essential. Historically, we have often seen quality regimes develop as a reaction to an emerging need, such as the investigation of an issue, the completion of witnessing or testing activity, or the approval of process documentation, rather than as a proactive engagement.

This mindset is a fundamental flaw and must change. The quality function brings a lot more to a project than the sum of these activities and its early engagement is advantageous in several ways. Most importantly, it gives the project the ability to create a quality regime that is properly resourced from the outset and is set up with two key factors in mind – compliance and efficiency.

Fundamentally, ensuring compliance from the get-go provides internal and external stakeholders with confidence that key aspects of the design, such as safety function requirements, have been objectively and independently verified.

Taking a whole-lifecycle perspective from project inception means a business case can be made for investment of time and money to de-risk future phases. Recent experience on a complex infrastructure programme indicates that early investment in inspection and commissioning is critical to avoid costly delays and expensive retrofits. This way, there is a clear line of sight through each stage – from project requirements, design, systems lists and schedules, to engineering, construction, commissioning and handover – ensuring verification and validation can be easily proven at each point.

This way of working enables a graded approach to commissioning and testing. Not all components and systems require the same rigour of testing. As such, early involvement of the team allows us to identify which items are to be fully tested (i.e., those providing safety or environmental protection) and those that can have a less onerous testing regime applied, as any issues that follow would be self-revealing and not compromise the installed process or its operation.

We have seen many examples where over-specifying quality requirements has restricted the ability to source materials, leading to additional and unnecessary costs and requiring significant work to justify re-grading – all of which causes delay, as well as cost added to projects.

Knowledge of the project delivery scope, regulatory requirements and timeframe for delivery, promoted by all members of the quality team, is vital in providing value to the project. In this way, the function ensures everyone is aligned to the mission of delivery against the standards that are demanded by the customer, regulatory bodies and the general public.

2. Establishing culture and behaviours

Delivering complex major projects to the highest standards requires getting the approach to quality right from the outset. A vibrant quality culture is at the heart of those projects which surpass expectations, delivering on time, to budget and creating social, economic and environmental value. There are two clear indicators of success – integrating quality into the programme from its inception, and a culture underpinned by visible endorsement from the senior leadership team, which cascades throughout the integrated project team.

The importance of taking the time to start in the right way cannot be underestimated. Right-first-time delivery requires early input from the quality team to shape the development of the programme, de-risking future delivery by identifying key processes and functional interdependencies from the outset. It is much better to set the right regime at the beginning, even if it means that mobilisation takes longer and costs more. This early investment in quality will pay dividends in the long run, avoiding unnecessary costs and delays down the line.

Timing is therefore critical, yet so is a well-resourced quality function, integrated with all other core disciplines and engaged at each phase, from pre-contract to mobilisation and manufacture. By maintaining momentum and focus on quality through each phase of the programme, all parties understand the quality grades and controls they need to address, and can adopt good practice examples, discussing this openly with the quality teams to achieve positive outcomes. This is particularly important as a contract shifts in phase e.g., from manufacture to construction and installation. We should pause and check that the resource and knowledge of the teams are still valid for the next phase.

The second key indicator of success is culture. Everyone has a role in assuring quality. By creating a ‘one team’ mentality, in which everyone is heard and feels empowered to follow their conscience, we develop a strong quality culture. This is critical to assure effective and efficient project delivery, anchored by a common understanding of what is required and what is important.

So how do we do this? Armed with the knowledge that culture and behaviours are the barometer of quality, at Costain, we recently developed an approach to measuring the impact of culture on performance for a defence mega-project.

We shaped a programme of regular employee engagement, spanning the core themes of leadership, compliance, competency, communication, and values and ethics. This was monitored through tactics including project-wide surveys, on-site engagement activities and leadership walks. Qualitative and quantitative data was then assessed against key quality performance metrics and used to identify opportunities to strengthen the culture.

This information was routinely provided to a newly formed ‘quality leadership forum’, made up of supply chain project directors, ensuring leaders were armed with the insights needed to drive change. With dedicated coaching, these leaders were able to model best practice and raise the profile of quality through data-led conversations and celebrating the team’s successes. Such high levels of engagement and commitment led to significant improvements in quality performance.

3. Embrace the power of digital

The foundation of a strong quality culture is the ability to establish clear standards in everything we do. Digital tools and processes can digitalise the documentation process and enable efficient capture of data in real-time. This is particularly useful in heavily regulated industries such as nuclear and energy where additional levels of documentation are needed.

To commission safety-critical systems, we must first ensure that safety functional requirements have been objectively verified as having been met and that the relevant verification documents, such as inspection and test plans, have been signed by an appropriately qualified and appointed person. All this requires rigorous documentation and records management and maintenance, in sync with the physical works. Completion is not achieved until this happens.

To support transparency and efficiency, we increasingly look to digital systems to manage documents and to improve tracking, traceability and simplicity. Digital tools and applications can also support in capturing proof and evidence at every stage of the project, meaning less delay and less impact on the schedule. For example, the introduction of remote inspections has had a significant benefit on some of Costain’s major projects. If proof and completed documentation are not available in a timely manner, it can have significant impacts, such as the ability for clients to achieve a licence to operate. Having rigorous and electronic solution capability allows any issues or gaps to be identified as early as possible, and rectified.

Digital solutions range from using modern electronic document management systems (EDMS) solutions to facilitate document submission, review, approval and tracking, all the way through to the use of BIM, digital twins, point cloud scanning and common data environments.

All of the above helps build a ‘single source of truth’, avoiding miscommunications and misunderstanding, which means that data is accurate, up to date and accessible. Using correct digital technology helps build up a picture of document deliverables that support schedule to avoid delays in works starting.

4. Standardise for predictability and sustainability

Production thinking at Costain draws on, but goes beyond, the principles of factory thinking. Production thinking applies to the suite of adaptable tools used to create the best results for clients and end users. It’s not about building in a factory, it is about achieving factory levels of performance.

This approach is based on transforming our business away from traditional complex construction and bespoke assets to standard products, integrated off-site, and simple, on-site assembly. Off-site modularised manufacture is one of the tools we commonly use, but production thinking is about the whole-asset lifecycle and the needs of the job in hand, not being prescriptive.

A modular approach to complex infrastructure helps to maximise the opportunity for offsite testing, trialling and commissioning of systems. Early investment saves long-term cost and reduces overall programme length by enabling simultaneous work streams.

Performing a modular build de-risks the likelihood of components not fitting on site. Although obvious, this ‘plug and play’ approach isn’t widely adopted due to the upfront investment required. It differs from the traditional approach, building more complete parts and installing them later, rather than working in sequence, and becomes even more powerful once integrated into a system.

Although the approach tests the supply chain’s ability to build, test, verify and validate, it increases collaboration, early involvement, and the ability to work in a concurrent manner. Having a physical asset and the documentation developing in parallel avoids a bow-wave of late-stage work, particularly installations, inspections and documents. It gives far more confidence in terms of how the components operate together as a complete system.

Once on site, working is more difficult and installation works can often over-run, with a knock-on-effect on other suppliers. In an ideal scenario, the project would have the minimum number of parts for installation on-site at any one time to reduce the risk of the project running over. Fewer activities on a live site in a busy construction environment also reduces the amount of verification required at site and the associated resources needed.

A systems approach to the verification and validation plans is vital to project delivery. This would set out clear links from high-level project requirements through to individual component testing and how these build up to evidence ‘building the right thing’, as well as ‘building it right’.

5. Establishing a systems integration facility

A best practice approach would be to provide a safe environment for modular build integration ahead of any construction works. Off-site integration testing gives all supply partners, as well as the client, an opportunity to test produced parts or sub-system modules in a practice environment. This approach has clear benefits, including:

- reduction of risk – minimising the risk of faults or re-work from components and sub-systems not working correctly together when installed

- better sequencing of works – a practice environment highlights any installation conflicts, producing improved sequencing of works and inspections. This can prevent delays, particularly if components must be installed, removed and modified before other activity can commence

- more efficient problem-solving – issues that occur in the systems integration facility are easier to solve as they emerge, rather than once on a live site.

Dynamic testing or checking of systems that include multiple disciplines coming together (such as mechanical and engineering etc) allows interfaces to be tested progressively with high confidence during the build. This should be incentivised across supply partners to maximise focus on a collaborative system build, rather than individual suppliers working in isolation.

Working to a schedule that only focuses on an individual contractor or discipline often leads to a mismatch in readiness and inability to complete systems and initiate commissioning. This in turn leads to inefficiency as teams are often stood down, works rescheduled at short notice and/or delays to fit the missing parts, all of which impact other activities in the programme. Commercially incentivising suppliers and disciplines to work collaboratively, while focusing on achieving progressive commissioning milestones, changes the focus from individual key performance indicators’ completion to the sub-systems achieving completion as part of the whole.

Overall, the ability to test real components with a supply chain that is in sync, physically and commercially, helps to better understand the works required to move to progressive commissioning.

Quality’s prominent role

Against the backdrop of the cost of living and energy crises, there is significant pressure on the government to spend public money wisely and for delivery partners to leverage infrastructure investment to deliver value in all its forms.

In this environment, quality should play an ever more prominent role. If a strong quality regime is established from the mobilisation phase of complex major projects, with cross-functional buy-in, we can minimise the risk of unanticipated costs or delays to the schedule.

Furthermore, by adopting a systems approach which identifies synergies across the whole programme lifecycle, through standardisation and the use of digital tools, we can de-risk the trialling, testing and commissioning of safety-critical systems and assure delivery to client expectations. This means eliminating waste wherever possible, while also creating social, economic and environmental value.

We’ll leave you with this final thought: quality is often the unsung hero of programme management. Yet given its significance and the potential for best practice to be shared across all sectors in our industry, a dedicated systems integration facility would be a strategic investment, creating a blueprint for efficiency which can be rolled out again and again. It would also act as an antidote to the skills shortage, showcasing the value of this complex area of engineering and providing opportunities for us to attract and train the next generation of talent.