Understanding the Big Picture to ensure successful project delivery

Author: Hazel Woodcock, chief systems engineer

Have you ever been involved in a project that struggled to set out the big picture? Did that impact the way you and your team could work effectively? Are the various project teams on your project, communicating effectively to ensure contractual requirements are met?

Systems engineering is a field of engineering management that focuses on how to design, integrate, and manage complex systems over the project life cycle. The discipline of systems engineering aims to solve challenges in already complex systems or design, manage and optimise systems for better decision making. Systems engineers are experts in understanding the intention of the system to then design the architecture that best supports these organisational and project aims. According to the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), “systems engineering is Big Picture thinking and the application of Common Sense to projects.”

However, the later the systems engineers are engaged in the project, the more limited the tools, methods and concepts they can feasibly deploy to help manage the various interfaces with the supply chain, the technology and the immediate delivery team. This process of looking away from technical detail to see the bigger picture, considering how individual assets, or in this context teams, work together to achieve the overall objective, is crucial to project success.

The reality of projects

Invariably there are multiple stakeholders involved in major complex programmes so implementing an interface management process that acts as a ‘mission control’ helps streamline communications and identifies the critical interfaces or connection points between parties or elements within the system.

In an ideal project scenario, systems engineers work with programme managers to achieve project success by having greater control and awareness of the project requirements, interfaces and issues as well as the consequences of any changes. Research by INCOSE indicates that effective use of the methodology can save 10-20% of the project budget.

Using systems engineering language, the component parts of what you are working on, the ‘technical interfaces’, will align perfectly with how you are working with your stakeholders, ‘the organisational interfaces. Also, in an ideal project, the culture is focused on the outcome of the whole system rather than any organisational or personal aims. The groupings of activities are therefore all loosely coupled i.e. interconnecting elements are dependent on each other to the least extent practicable which prevents an issue affecting the system as a whole. For example, if one element fails, or needs to be redesigned, the consequence is far less reaching than if there were multiple interdependencies.

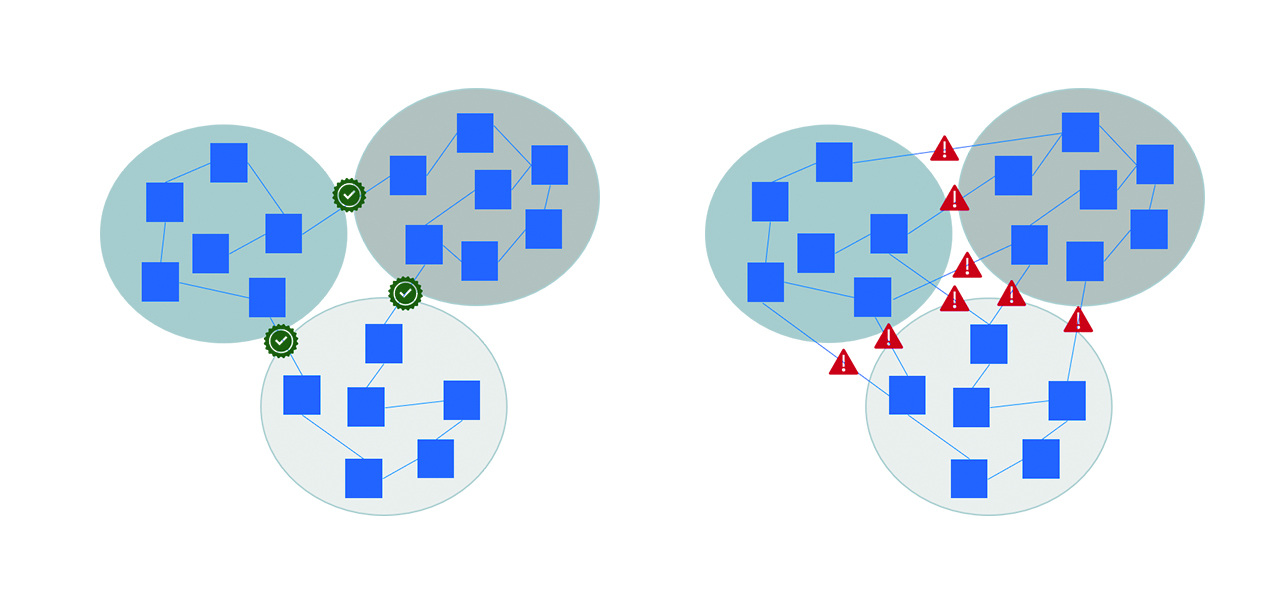

The diagrams below show common boundaries where direct contact between two different activities (such as culture, environment) occurs and where information is exchanged. In figures 1 and 2, you can see the number of connections between the three systems. Figure 1 would be a healthy project; resilient due to loose coupling; productive due to the alignment of interfaces; efficient as everyone pulls in the same direction. Figure 2 can be more common for large projects where interfaces are not aligned and there is tight coupling which means multiple connections that have an impact on exchanges of information or energy.

There are many reasons why this tight coupling is the default position, but we can still strive to come closer to the ideal. The benefits would be projects delivered at lower cost, shorter time, and higher quality, all supported with collaborative behaviours and culture so there is real value in progressing towards this desired outcome.

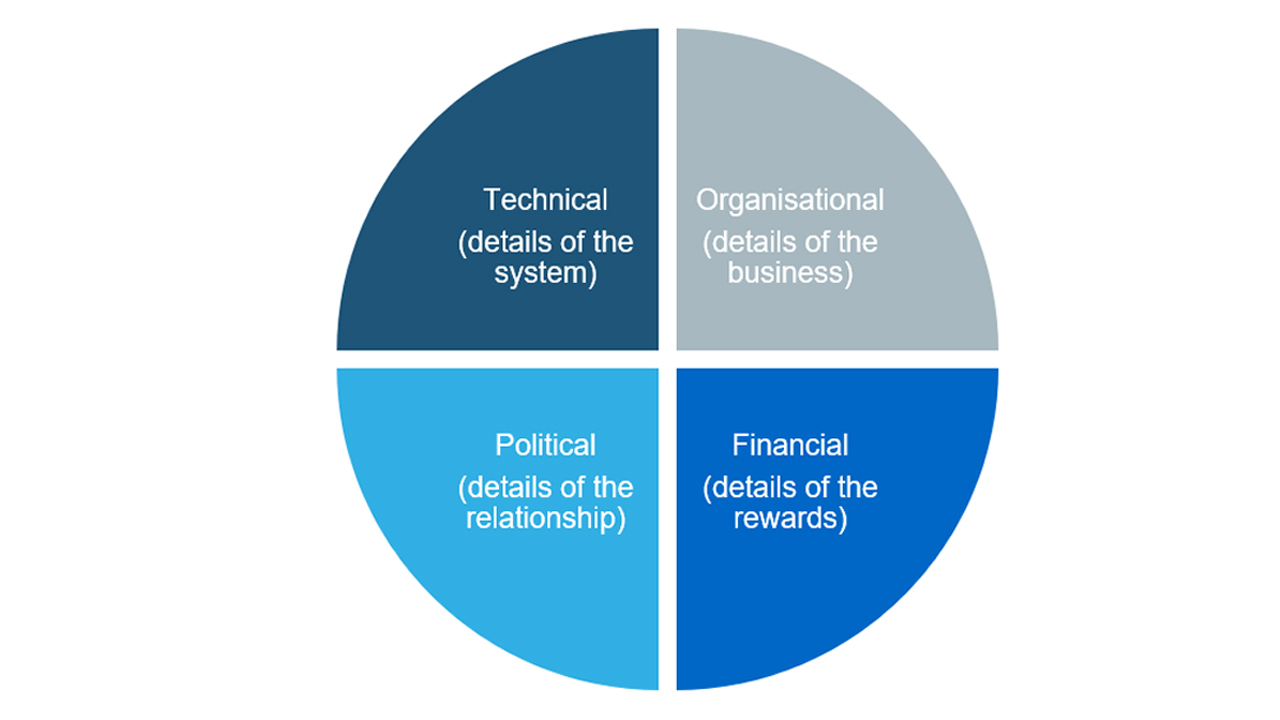

The key boundaries and connections for critical national infrastructure

Technical boundaries

The technical boundaries should be simple to put in place. It would make sense to align everything else to these boundaries as all boundary types are included in a major asset or infrastructure programme.

Ideally the system would be analysed in the project concept phase and the architecture drawn to minimise coupling and maximise use of standardised interfaces and the re-use of existing work. In reality, problems can occur and compromises need to be made.

Clear, well documented and well managed interfaces are essential to the efficient progress of a major complex programme as they promote project stability and operational effectiveness. It’s essential that every team in the design and development process has clear knowledge of what their inputs and outputs will be. Visibility and understanding of the interfaces is critical.

Political boundaries

A large system, or system of systems, will often impact, or be impacted by, political concerns. Where a system is publicly funded there is always pressure to buy the ‘home-grown’ solution and to share the work between regions that require investment. Where the system is an international collaboration there is pressure to divide the work between collaborating nations.

These political boundaries are less important to the final deployed system, but politics are not always logical, subject to change for non-project related reasons, and are often most important in sourcing funding for the development and realising the project.

Organisational boundaries

When the technical decomposition and political boundaries are decided, the work is apportioned to different organisations and departments. These organisational boundaries are the walls of silos. Cooperation across these boundaries can be reduced due to cultural differences, unclear accountability and responsibility assignments, tribal mentality, data boundaries, empire building and other undesired behaviours. This problem persists without incentives to behave otherwise.

Financial boundaries

The financial boundaries are part of the organisational boundaries. Each organisation gets paid if they do their bit right. There can be significant financial incentives to optimise a subsystem at the expense of the wider system, and there is rarely a financial incentive to help a different organisation, an SME or part of the supply chain or even the community the project is potentially impacting.

Mismatched boundaries can lead to confusion over accountability and responsibility

The conceptual, logical, and physical architectures may have very different forms, and this may fuel a mismatch of boundaries. We should not compromise the technical solution based only on a desire for fully aligned boundaries, rather we should work to reduce the impact of those misalignments and consider some scope for fluidity in the structure of organisations that are working to deliver the project.

In order to start on the right foot, an ‘interface definition owner’ is a key player in setting up the required architecture on any complex project or programme. The above boundaries and interfaces all exist and it is obvious that if you have a technical system boundary, the organisational and financial boundaries should ideally align. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always happen that way. Mismatched boundaries can lead to confusion over accountability and responsibility and are difficult to re-align without a change in leadership behaviours and team culture.

Boundaries can move during a project as milestones are reached. We saw Costain’s major asset support life cycle in an earlier article from @NickJacques, and there are a number of obvious opportunities here for boundaries to move and become mismatched. Design, production, operation and maintenance all affect the owner of a subsystem and as this moves, the financial and organisational boundaries may shift at different rates or not at all. There may also be new boundaries created as an integration team are rewarded, formally or informally, for finding fault with production or design output leading to an ‘us and them’ mentality.

Removing technical boundaries

We can’t remove all the technical boundaries, but we can decide where to put them. Creating subsystems that are loosely coupled, that is where there is as little dependency on the interfacing subsystems as possible, will reduce the complexity and risk.

Removing political, organisational, and financial boundaries

The political, organisational, and financial boundaries are always going to be present with a major project, so the issue is again not about removing, but aligning them. Understanding where these boundaries are mismatched to each other and to the technical boundaries makes the potential problems visible and therefore more manageable.

Optimising one component can lead to sub-optimising the whole

The problems arising from boundaries centre around ownership and communication and simply recognising a boundary for what it is can ease these problems. Leaving boundaries misaligned without active management to encourage desirable behaviours, leads to a systemic problem that cannot be solved by a few diligent individuals.

One way to address silo mentality is to increase visibility through sharing live and traceable data in the supply chain. Engineering data is an obvious candidate, but project progress, integration issues, and simple contact information also help. When we share data, we stand a better chance of seeing how to optimise the whole.

The second way is through shared ownership of the outcome (sharing the whole problem risk and reward). This is a healthier approach for the stakeholders as it encourages behaviours that lead to the right result for all parties.

Getting the right result for the end system means collaborating and acting in the interest of the bigger picture. My colleague showed how rolling wave planning can be effective to manage funding cycles on particularly long programmes. Nick Jacques explained in an earlier article how understanding the desired outcome can help.

Overall, the goal is a ‘one team’ mindset, with or without a formal joint venture organisation. Know where the boundaries are, know who the stakeholders are, know where the money flows, but work in an open 'zero defects attitude' culture.

Are your boundaries aligned? Do you know what is ‘over the wall’? Have you created a low risk resilient enterprise or a tightly coupled and brittle system of systems?

Link list

- Discover more about Costain's systems thinking approach

- Read article: Delivering decades of operational efficiency and certainty with through-life thinking

- Read article: Rolling wave planning (part one) – the ebb and flow of planning major projects

- Read article: Rolling wave planning (part two) - can it break on a fixed year financial funding model?